As a topic in general, good questioning has many examples in every field. It pays to study the process of questioning as a separate subject, as if you were going to design an FAQ for your skill. Not only can it make you a better learner, but a better teacher.

If you are a teacher, you know there are multiple advantages about encouraging questioning from the start. Questions from a student show a teacher their student's range and style of thinking. Questions point in the direction of the answers. In fact, questions can imply a limitation of what kind of answers that are possible to find. Better questions open up a rich field of personal discovery.

How do you ask a really good question?

As a student, you can ask any question to get started. Sometimes the first questions that come off the top of your head aren't the most appropriate, but everyone has to start somewhere. Most teachers understand this.

As a learner, to ask a really juicy question, you first have to listen carefully to learn any "lingo" about the topic. So the best questions to start with are often about the specialized use of terms being used.

The other skill that's good to develop as a questioner is being able to tell the teacher the best way that you learn by indicating acknowledgment you are following them. It's useful for the teacher to know when the student is on "over-load, please change tactics now" or "I've got it, go on" to the teacher.

Some learners believe some kinds of questions might be insulting or too challenging for the teacher.

At first, even in a private lesson, most students seem to want a teacher to "lecture" them. They want to let the master talk. The teacher saying something to preface or frame a lesson might be appropriate in some cases. But what if the teacher doesn't really want to go on about the topic; what if they want their student's involvement from the very beginning?

Some teachers address this desire by doing the asking themselves, and then answering their own questions. They hope that the students will get the idea of what kind of questions to ask and starting to ask questions themselves. However, students can misunderstand that questions posed by the teacher and then answered are merely rhetorical ones; that the teacher is asking these questions to show off their knowledge. The students may imagine that the teacher would never ask a question that they don't already know the answer to. What to do when the teacher finds that students resort to parroting or restating the teacher's questions with other motivations such as to gain approval?

How can a teacher encourage learners to get past their misconceptions that particular issues, communications or questions are somehow "forbidden" without losing ability of being able to direct the class? Part of being a teacher is the skill of pulling together the attention of the group. There are some assumptions that create problems with encouraging this activity in learners related to respecting the teacher; especially in a large class situation. What to do when students seem to believe that they are being encouraged to deliver certain questions that cross the line of impolitely questioning the ability of the teacher to teach?

It's very tricky to ask a question that will point in an entirely new direction. Questions can imply that there is one answer, rather than a multiplicity of answers. It's also easy to think that just because you have come up with an answer to a question - that this one answer is enough of an answer.

Fantastic and personally meaningful questions sometimes need quite a bit of personal experimentation to adequately explore their potential. Sometimes this kind of question can become a sort of "virtual question" that many actions of exploration are continually answering during the course of life.

- How can you encourage your students to ask really good question of the teacher?

- How can a teacher get around student's misconceptions about the nature of authority, for instance, without inviting disrespect? (We're talking about adult learners here.)

Instead of my lecturing, here's an account from many years ago about a teacher of mine who I considered to be a master. In this case, she was teaching Alexander Technique, but this relates to asking questions concerning any skill.

My teacher was in her late eighties here. She's almost five feet tall. Classes could be huge; sixty to eighty people in one room. The advantage was that the workshop lasted for weeks. The disadvantage was that people figured it was too early in the workshop to dare to risk anything in front of everyone else.

My teacher was too polite to be overt about what must have been some frustration beyond kidding the group, "What do I have to do to get some questions and thinking out of more of you people, do a jig?" Most often, laughter, but no daring questions. The humor did have some effect to loosen people up.

The experience of feeling a new perceptual assumption that Alexander Technique delivers is unsettling to many people. A master of an art can sometimes come across as frightening or magical. In this case, people were both attracted and intimidated. This little old lady could shake people's foundations; pull the carpet out from underneath their very sense of self. So the group treated her with "respect." For some people, this turned out to be a kid glove sort of unquestioning loyalty and agreement.

This little old lady named Marj Barstow hated that. She had a number of ways of dealing with it. One was to invite different people to get up in front of the class for a "private" lesson with her... with everyone else watching. While working with someone she would ask, "So you see that little difference? Can someone describe what they see?" She wouldn't go on until someone described it.

That's how she taught us to see very subtle indications of motion or a lack of movement. That also taught us to ask ourselves what these indications meant in each specific situation with each different person. It was also how she embarassed people, and then showed them the way out of the crippling emotions of stage fright, embarassment and being completely tongue-tied.

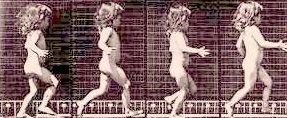

She might ask the group to move in slow motion to illustrate a crucially pivotal point that influenced that entire outcome of what someone was trying to do. Then we learned how to integrate the special points with the whole, normally speeded action again.

These examples of techniques to encourage questions are, (or should be) commonplace to any teacher. The one I'll tell you about next surprised me, because I regarded it as being positively sneaky.

My teacher took me aside and told me that she appreciated having me and a few other people in the class. She said that it was because we'd pipe up with questions that nobody else would dare ask. She then told me a story about how she didn't understand when another student accused her of putting them on the spot by singling them out, inviting their participation. This is what made me realize that she was asking my permission to deliberately put her "on the spot" by bringing up what may be forbidden as defined by the group of students. This little old lady had some unusual ideas in her field about how her skill should be taught. People seemed to be avoiding asking her specifically about what made her ways different. I decided that she wanted me to break the ice, so to speak, for the rest of the class.

Essentially, she gave me license to be planted as a sort of "sacrificial fool" in the forbidden questions department. People would stare at me with open mouths and shocked looks on their faces when I'd fire off these questions that nobody else would dare say.

It pleased the teacher and myself immensely - I felt as if we were conspiring together. After those kind of questions were in the air, class would get much more interesting. Other students would then started to ask the questions that were very important to them personally.

So if you are a teacher, don't be above encouraging one of your students to act as a 'secret plant' in the classroom! Certainly - if you've got any comments or questions to ask me - please speak up now!